Enigmerica Election -- Mea Culpa

In one of my previous posts, I was incorrect about my solution. In brief, the riddle is this:

In an election where two candidates both expect to get 50% of the votes, 80% of the votes will be counted on election night, and the remaining 20% will be counted later. What is the probability that the leader on election night will lose?

Where the old solution went right

There was some text about random and independent trials, and the number of voters being very large. The first bit allows us to assume that these are Bernoulli trials and follow the binomial distribution. For example, if I give you a fair coin, what is the probability that you flip heads? If you said 50%, give yourself a pat on the back. Now, what if I tell you that before I handed you the coin, I flipped it 3 times and got 3 tails, does that change your answer? If you said no, have a cookie too (after you are done patting yourself on the back). The coin has no memory, and past results don’t influence future flips.

The fact that we have large numbers of voters means that the Central Limit Theorem applies. In short, we can assume the binomial probability distribution can be estimated using the normal distribution. (That’s our friends dnorm and pnorm again…if you don’t remember, look back a the old post.)

Where the old solution went wrong

Right here:

Note, that we can simply use the standard \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma = 1\) choices for the normal distribution as the actual percent margins can be normalized, and the scaling factor drops out of the margin inequality above.

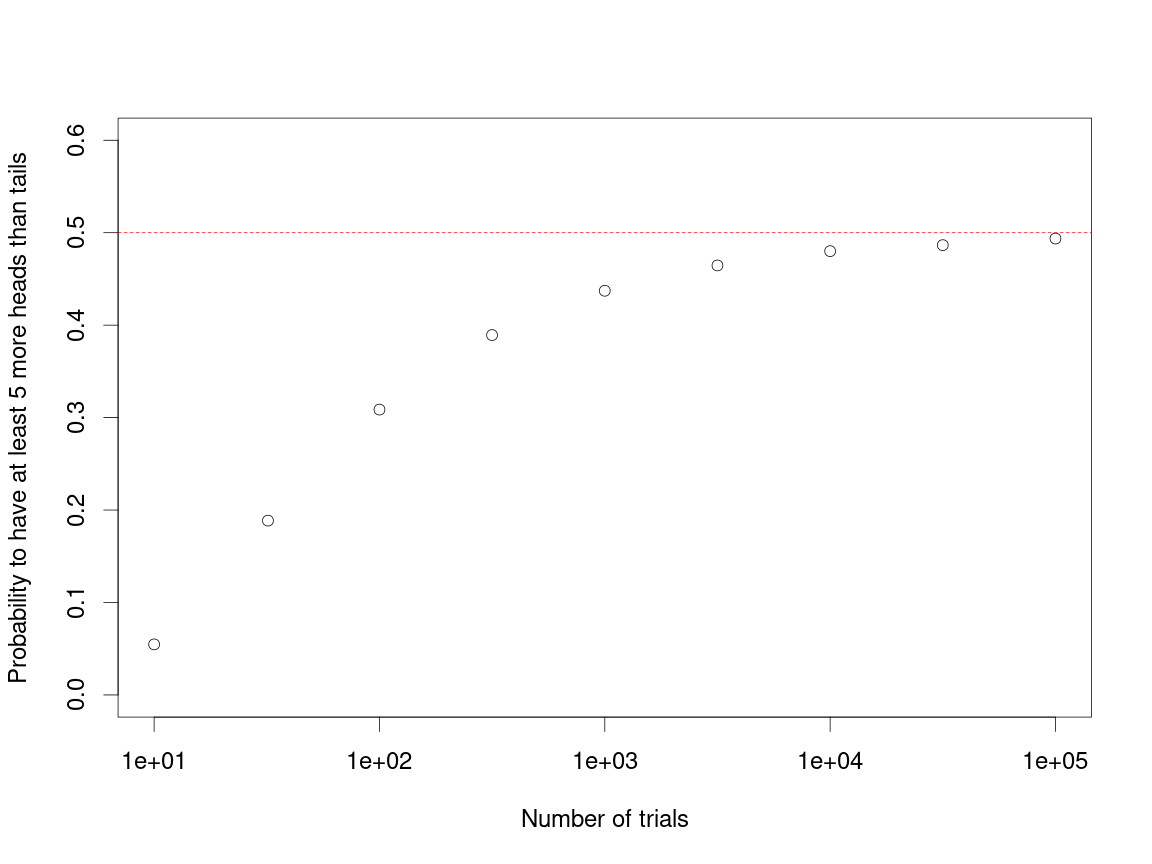

The variance in the distribution should depend on the number of trials that we run. For example, let’s just consider flipping a coin \(N\) times. What is the probability that I have at least 5 more heads than tails for different values of \(N\)? This condition is met when the number of heads that I flip \(k\) obeys this inequality:

\[k \geq \frac{N}{2} + 2.5\]Note, the pbinom function is much like the pnorm function noted previously. Let’s look at how probable a margin of 5 heads is as \(N\) increases:

N = round(10^(seq(1,5,by=0.5)), 0)

kmin = N/2 + 2.5

pMargin5 = pbinom(kmin, N, 0.5, lower.tail = FALSE)

par(cex=2)

plot(N,pMargin5,log='x',xlab='Number of trials',

ylab='Probability to have at least 5 more heads than tails',

ylim=c(0,0.6))

abline(h=0.5,col='red',lty=2)

Now, while you might think that this is fine since we are in a large \(N\) regime, this is a close race, and marginal differences shouldn’t be neglected.

Let’s fix things

I want to reframe this a bit. Let’s start by looking at the probability distribution that a candidate will get \(x\) votes in a given counting of \(n\) votes. For the binomial distribution, we know that the mean \(\mu = np\) and the variance \(\sigma^2 = np(1-p)\) are well-defined. Now, we can use these to approximate a normal distribution (this is that Central Limit Theorem I mentioned earlier):

\[d(x;n,p) = {n \choose x} p^x \left(1-p\right)^{n-x} \approx \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi np(1-p)}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\frac{\left(x-np\right)^2}{np(1-p)}\right)\]We can again change \(x\) from an absolute vote count to a marginal vote count. Instead of having a mean of \(np\), it will simply have a mean of zero:

\[d(x;n,p) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi np(1-p)}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \frac{x^2}{np(1-p)}\right)\]On the first night, \(n = 0.8N\), let’s call that margin \(x_1\):

\[d(x_1;0.8N,p) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi 0.8 N p(1-p)}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \frac{x_1^2}{0.8 N p(1-p)}\right)\]And on the subsequent count:

\[d(x_2;0.2N,p) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi 0.2 N p(1-p)}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \frac{x_2^2}{0.2 N p(1-p)}\right)\]So for the result to flip, one of two conditions needs to be met:

- \(x_1 > 0\) and \(x_2 < -x_1\)

- \(x_1 < 0\) and \(x_2 > -x_1\)

Ok, now we are getting close. We just need to figure out what to put in for sigma. Again, the absolute number shouldn’t matter. Let’s define:

\[\sigma^2 \equiv 0.2 Np(1-p)\]and use this to scale out the \(N\) from these distributions, which we don’t know anyway:

\[d(x_1;0.8) = \frac{1}{2\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{x_1}{2\sigma}\right)^2\right)\]and

\[d(x_2;0.2) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{x_2}{\sigma}\right)^2\right)\]So the standard deviation for the vote margin on election night is double what it will be for the mail in vote. Let’s put that in the code and integrate numerically:

dm = 0.0001

margins = seq(0,1000,dm)

probFlip = 2*sum(dm * dnorm(margins,sd=2) * pnorm(-margins,sd=1))(Note, I’m multiplying by 2 in the last line above to take care of the fact that we don’t care which candidate starts out ahead on election night.) The probability that the result flips is 14.76%. (Here’s more digits if you want them: 0.1475936.)

Extensions:

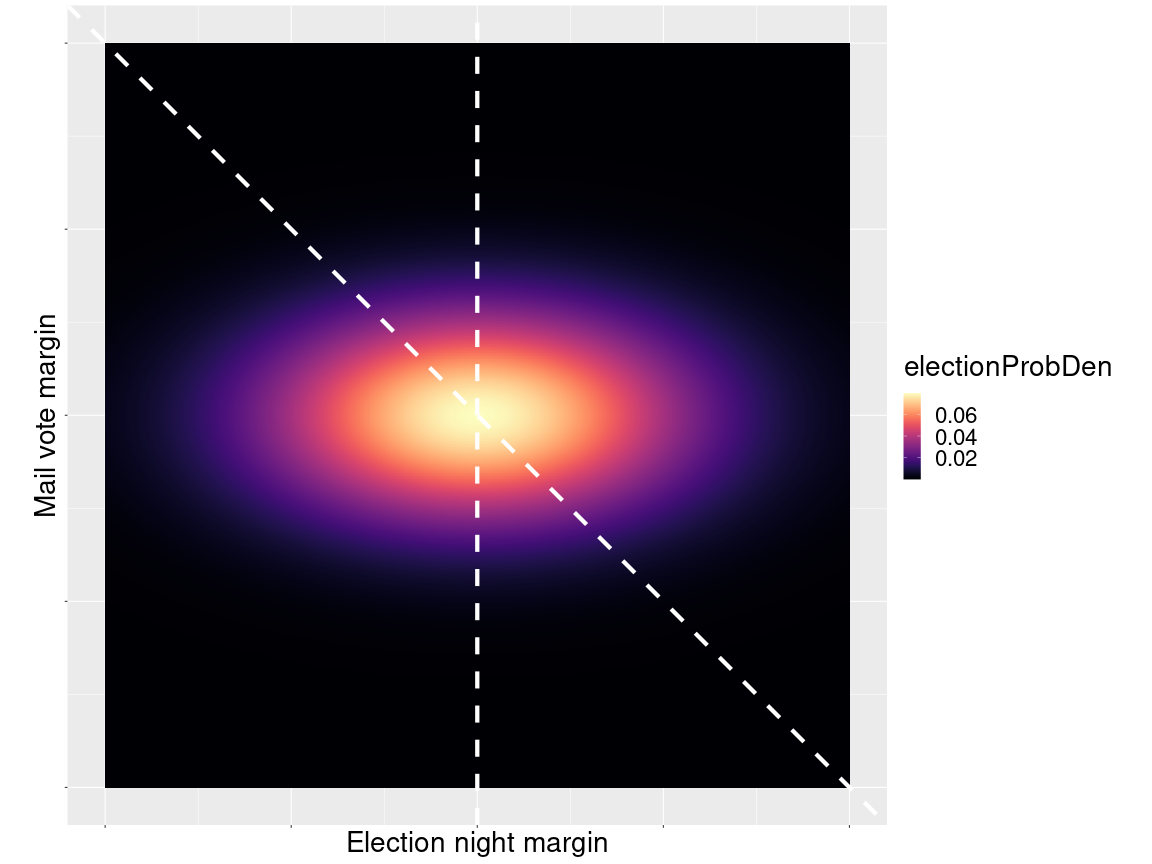

There was a really cool heatmap on the Riddler Solution page that I totally want to copy. For this, we need to create the 2D probability function

\[P(x_1,x_2) = d(x_1;0.8) d(x_2;0.2)\]And now let’s create that function in R and make a heatmap:

electionProbDensity = function(x,y){

epd = dnorm(x,sd=2) * dnorm(y,sd=1)

return(epd)

}

plotMax = 5

plotRange = seq(-plotMax,plotMax,length.out=1000)

plotDat = expand.grid(X=plotRange, Y=plotRange)

plotDat$electionProbDen = electionProbDensity(x=plotDat$X, y=plotDat$Y)

ggplot(plotDat, aes(X,Y,fill=electionProbDen)) + geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis(discrete = FALSE,option="A") +

xlab('Election night margin') + ylab('Mail vote margin') +

theme(axis.text=element_blank(),text = element_text(size=28)) +

coord_fixed() + geom_vline(xintercept=0, color='white', lwd=2, lty=2) +

geom_abline(slope = -1, intercept=0, color='white', lwd=2, lty=2)

We are integrating over those triangular regions marked out between the dashed lines.