Counting my marbles before I lose them

The riddle

From Matt Enlow comes an original puzzle of his that previously appeared in Math Horizons. (At first it may seem like there’s information missing, but I assure you that is not the case.). A bag contains 100 marbles, and each marble is one of three different colors. If you were to draw three marbles at random, the probability that you would get one of each color is exactly 20 percent.

How many marbles of each color are in the bag?

Functions and background

I’m sure that there is an analytic solution to this. But, BRUTE FORCE will work too. We can be a little smart. I’m going to assume that we have red, green, and blue marbles and denote their numbers to be \((n_R, n_G, n_B)\) respectively, and I’m going to define \(N \equiv n_R + n_G + n_B = 100\). There are six ways that we can draw marbles of each color, so the probability to get one marble of each color for any bag with three colors of marbles is:

\[6 \frac{n_R n_B n_G}{N(N-1)(N-2)}\]Let’s code this up in a function:

probAllThree = function(k,l,m){

N = k + l + m

prob = 6 * k * l * m/(N*(N-1)*(N-2))

return(prob)

}Results

Let’s just loop through all the possibilities:

output = NULL

for(nRed in 0:100){

nBlueMax = 100 - nRed

for(nBlue in 0:nBlueMax){

nGreen = 100 - nBlue - nRed

prob = probAllThree(nRed, nBlue, nGreen)

tst = data.frame(nRed, nBlue, nGreen, prob)

output = rbind(output, tst)

}

}Now let’s look at the cases where the probability is equal to 20%

output[output$prob==0.2, ]## nRed nBlue nGreen prob

## 1947 21 35 44 0.2

## 1956 21 44 35 0.2

## 2962 35 21 44 0.2

## 2985 35 44 21 0.2

## 3520 44 21 35 0.2

## 3534 44 35 21 0.2So, we have to have 21, 35, and 44 marbles of each color for this to work. Of course, the colors you choose are up to you.

Extensions

I’m just curious, what’s the maximum probability and when does it happen? My intuition is that there should be some sort of symmetry like \(n_R = n_G = n_B\), but not quite since 100/3 is not an integer.

maxProb = max(output$prob)

output[output$prob==maxProb, ]## nRed nBlue nGreen prob

## 2839 33 33 34 0.2289796

## 2840 33 34 33 0.2289796

## 2907 34 33 33 0.2289796So my intuition is right, the answer is to make the number of marbles as equal as possible.

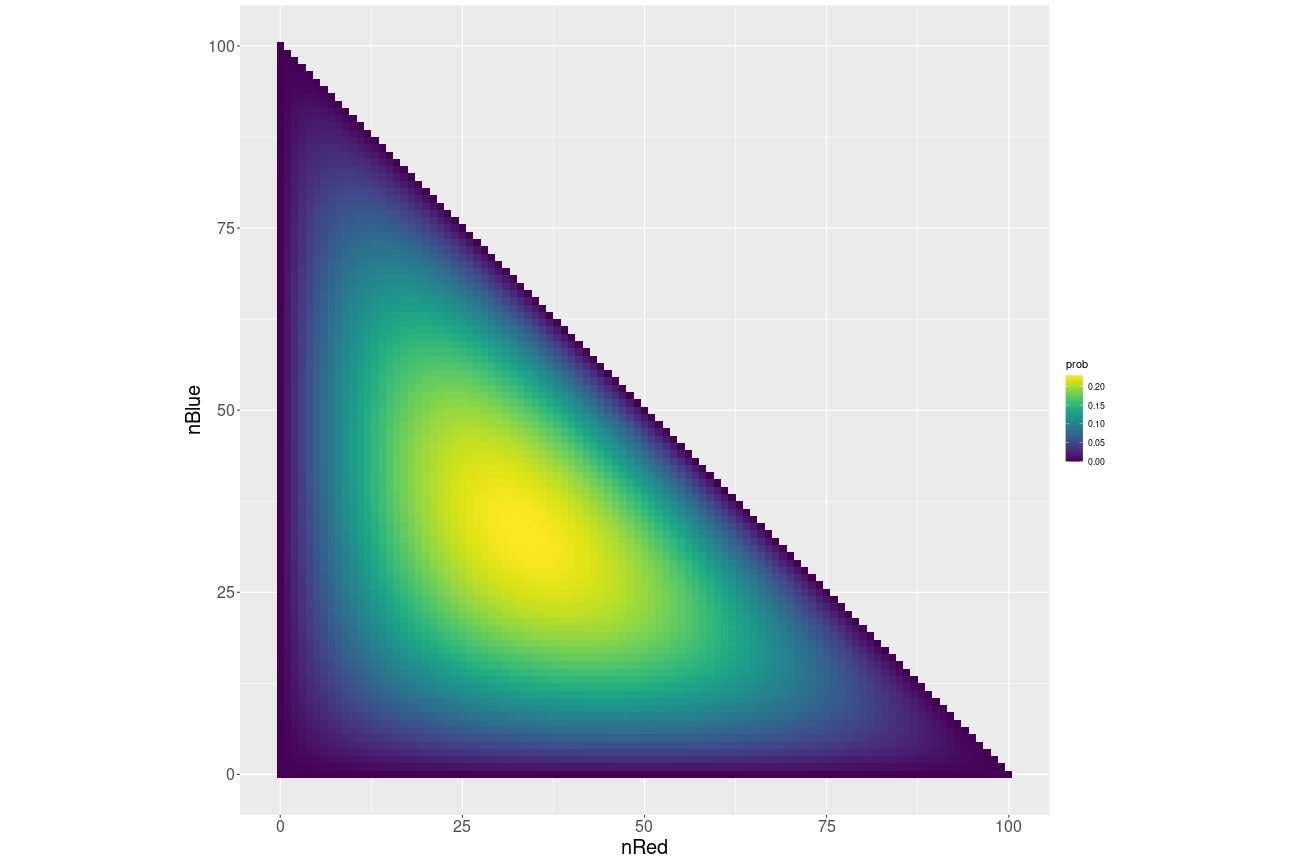

I also want to see a heatmap of what this probability looks like. It should be quite symmetrical. (Indeed it should be able to be reflected about a line with slope = 1.)

ggplot(output, aes(nRed, nBlue, fill=prob)) + geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis(discrete=FALSE) +

theme(aspect.ratio=1, axis.title=element_text(size=20), axis.text = element_text(size=16)) +

coord_fixed()

This makes sense. The probability is low when we have very few reds (left edge of triangle), very few blues (bottom edge of triangle), or very few greens (hypotenuse of triangle).

Just for fun, does the same ratio of marbles hold for larger values of \(N\)? (For example if I have 210, 350, and 440 marbles, is there still a 20% chance we get one from each color?)

probAllThree(210,350,440)## [1] 0.1946235Not quite…I didn’t think so. I can’t easily change marble numbers into probabilities in the above expression. We just have too many -1’s and -2’s running around in the expression to say that it should just scale up. If the denominator was directly proportional to \(N^3\) in the above expression, I would expect this to scale since I could then define \(p = \frac{n}{N}\) and have things cancel out of the expression. As it stands, we can do that to some degree:

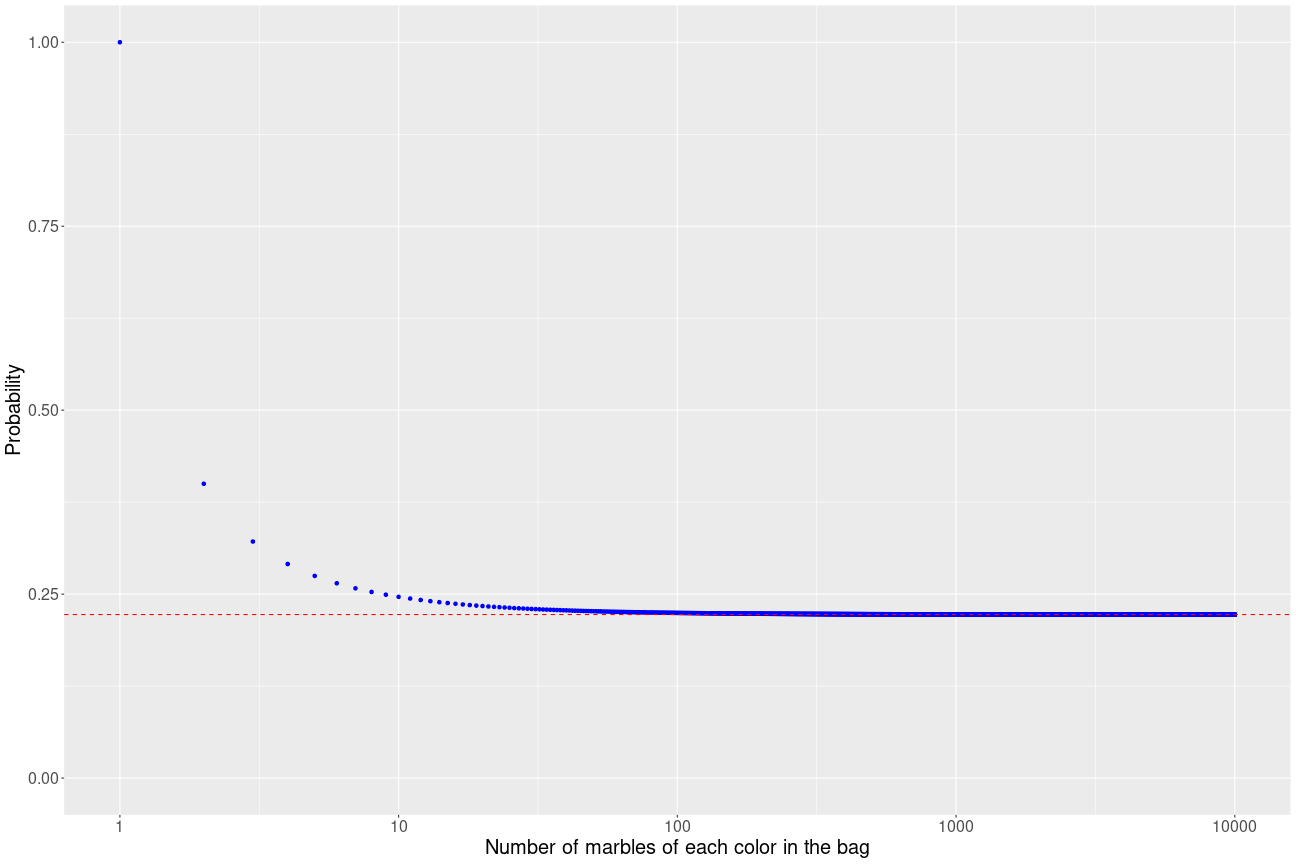

\[6 \frac{n_R n_B n_G}{N(N-1)(N-2)} = 6 \frac{n_R n_B n_G}{N^3} \left(1-\frac{3}{N} + \frac{2}{N^2}\right)^{-1} = 6 p_R p_B p_G \left(1-\frac{3}{N} + \frac{2}{N^2}\right)^{-1}\]The term in the parentheses will approach 1 as \(N\) gets very large. As the number of marbles grows this term can be ignored, and the probability will just be \(6 p_R p_B p_G\). If we further restrict ourselves to the case where the number of marbles from each color is equal, then we can set \(p_R = p_B = p_G = \frac{1}{3}\), and the probability becomes:

\[\frac{2}{9} \left(1-\frac{3}{N} + \frac{2}{N^2}\right)^{-1}\]This is indeed 1 for \(N=3\), and below is a plot of how it changes. The red line on the plot below is at \(\frac{2}{9}\) for reference. (Note the log scale on the x-axis).

n = 1:10000

p = probAllThree(n,n,n)

ggplot(data.frame(n,p), aes(n,p)) + geom_point(color='blue') + scale_x_continuous(trans='log10') +

geom_hline(yintercept=2/9, linetype='dashed', color='red') +

theme(axis.title=element_text(size=20), axis.text = element_text(size=16)) +

xlab('Number of marbles of each color in the bag') + ylim(0,1) +

ylab('Probability')